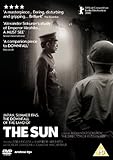

Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Sun (2004) Film Review

Alexander Sokurov's third, and possibly final, film in his series of historically significant totalitarian leaders, following Moloch (Hitler) and Taurus (Lenin). After watching The Sun, I'm looking forward to seeing the previous films.

In an interesting departure from political drama, Sokurov chooses to pore over the details of one of the final days of Emperor Hirohito (a sublime Issei Ogata) at the end of the Second World War, after the Allies have silenced resistance with the atomic bomb. The day begins as his butler serves breakfast on a glass-bottomed tray, establishing tone, mood and pace. The Emperor is clothed with an ecstasy of fumbling, and the day's events are explained, and unfold.

In a delicately observed movie, we learn the layout of his day, with only two hours devoted to dealing with his duties, as he meets with the cabinet. His defence minister, while upholding the national pride, weeps as he relays news of the crushing losses, realising, but never stating, the folly of placing such emphasis on the belief and fortitude of the Japanese people.

The film paints the Emperor as a capable student, a quiet, internalised man, whom "every child" in the Empire of Japan regards as "God in the flesh", who studies marine biology and devotes time to poetry, writing and photographs, which include memories of the family, the Empire and a separate album for American film stars.

The Sun is a fascinating film, rich in unspoken detail, a deep psychological conundrum of this man who renounces his godhood, taking upon himself the shame of defeat. The people are largely ignored, other than a moment where we travel to the US command station, visiting the devastation bequeathed upon the Empire, as his subjects salvage their belongings out of firebombed homes. Surprisingly, the film does not lack a sense of humour, invoking the dry, refined wit of a man bequeathed the duties of divinity.

There is a terrific scene when, after admitting defeat and dining with General Macarthur, it is time for the Emperor to leave. He faces the door, examines its handle contemplatively, before realising what he must do. He opens the door. And then it strikes you with the force of a blow. This is the first time he has ever done anything for himself.

As he announces the renunciation of holy powers, his manservant is continually with him - not even a hard slap to his face can deter him from his reason for being. It is through this, and the low-key ending, that we feel the great loss of the Imperial keystone of the Japanese honour and class system. The Emperor is finally free as a man, ensuring Japan's survival. But at what cost to the psyche of the people?

Reviewed on: 24 Aug 2005